The Living and The Dead: Understanding Silence

In numerous literary expressions, down the ages, there has been a constant suppression of the voice of the female counterpart. This indoctrination of the mind, to equate silence with virtue takes on a different turn if this is understood as a mode of deflection as aptly pointed out by Sigmund Freud. His meticulous study of the two popular fairy tales by Grimm Brothers, “The Twelve Brothers” and “The Six Swans” emphasizes the presentation of female silence as a strategic deflection of death. “It would certainly be possible to collect further evidence from fairy tales that dumbness is to be understood as representing death”1. What expands such a theoretical assertion to a universal dimension is Freud’s power of superimposing his theories of individual psychic conditions on modes of discourse that appear to be linear and non-ambiguous. In fact one might even think that his legendary conflict with Jung regarding the presence of a “Collective Unconscious” had no reason to be so violent as Freud himself had (perhaps unconsciously) banked on a presence of universal psychic condition in dealing with the literary texts coded with archetypal significations.

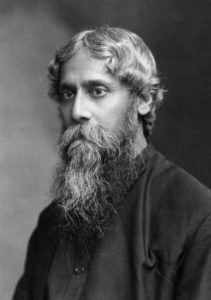

This universality of Freud’s contention is established in a stronger way if we consider his theory with reference to a social framework, belonging to a geographical location far removed from Freud’s own area of practice. In a celebrated short story by Rabindranath Tagore, there is a direct assertion of silence interposed with death. In Tagore’s “The Living and the Dead” what emerges as a constant motif is the representation of life as a metaphoric construct of silence where conventionally death is taken to be a fitting conclusion. However, the central focus of this paper’s attention is towards the denial to accept such formulations of death as a conclusive ending. The author focuses on the difference between death as society sees it and death as a real point of departure from life. At times it becomes uncanny in the implication of dissolution of these boundaries not just externally but within the individual’s psyche.

In the transformative moment as Kadambini came back to consciousness, in the hut of the cremation ground, she faced a challenge of believing in her own existence. She became capable of a momentary relaxation of her repressions:

At this thought, all the bonds were snapped which bound her to the world. She felt that she had marvelous strength, endless freedom. She could do what she liked, go where she pleased. Mad with the inspiration of this new idea, she rushed from the hut like a gust of wind, and stood upon the burning ground. All trace of shame or fear had left her.

The “Self” turning into “Other”

At the same time a constant psychic pressure made Kadambari in “The Living and the Dead” see herself as an altered creature, implying a sense of negation. It is as if she needed to completely discard her controls to make the innermost anxiety and will to power embedded in her id surface to prominence. This can happen only at the moment when the super-ego loses its external component –- the moment of isolation from social codes .However at this precise moment her ego began to feel the pounding impact of her anxieties embedded in her Id, anxieties that were a consequence of a constant repression of both Will to Power and Libido. Her life-long lack of both sexual and maternal fulfillment that found solace in the displaced maternal love for Sharadashankar’s son and her repressed desire to control her life beyond the clutches of society surfaced to prominence that primarily shocked her.

The fact that she chose to go to her childhood friend’s house can be seen as a psychic refusal to accept her inner desires as normal. At the same time it could be that she yearned for the blissful state of childhood, a pre-Oedipal state of innocence whose only external manifestation was Jogmaya’s memories and her household appeared to be emblematic of that. This is reinforced by the fact that she had no living relative whom she could turn to at this moment of distress. Yet, even after her reunion with her friend, so powerful were the forces to suppress herself that she ended up refusing her whole identity as her own:

She could not run away from her own presence… Kadambini was most terrified of what lurked inside her, not of what lay outside.

However the profundity of her neurosis becomes evident when she openly declared her alienation and difference from the “normal” inhabitants of the earth.

You laugh, you cry, you love, you’re occupied with your own affairs, while I just look on… you’re afraid I’ll bring some evil into your happy home; and I too don’t seem to relate to any of you.

Her inability to relate to the living world and her unconscious declaration of envy is, ironically not entirely her own responsibility. She was rather a victim of what Lacan would have called “The Symbolic Order”2, of social and cultural codes controlling her assessment of herself, codes that are beyond the control of her mental frame. Her situation was beyond the scope of any conventional linguistic articulation and hence she became doubtful of the very meaning of her existence. Death was not seen as a termination of life-processes but an undeniable fact solidified by social rituals and other people’s conceptions. Despite being instinctively aware that she was alive, she is unable to deny the expectation of society that considered her to be dead:

She recalled her last moments in Sharadashankar’s brightly-lit room, and compared her present solitariness in this dark, desolate remote place of death. I have no place in human society, she felt convinced. I am nothing but a fearsome evil presence—my own ghost.

Whatever relaxation was operative at her moment of freedom and alienation in the cremation ground began to subside as the super-ego re-emerged to get hold of her consciousness. This proves pointedly that the super-ego, at least in context of 20th Century Bengali women was entirely a social construct, enforced by one’s proximity to society.

Instinctively aware of this, Kadambini attempted to withdraw from social environment. However, she failed to do so because, despite what society thought, she was not dead and hence a part of the living world. If we digress a bit and look at what Jogmaya and her husband felt at the moment before they fainted at the final words of Kadambini, we might be reminded of Freud’s essay “The Uncanny” where he equated the evocation of an uncanny feeling with the process of de-familiarizing the familiar. Kadambini, the childhood friend of Jogmaya transforms, in the latter’s mind to an apparition in spite of the similarity of her external appearance. Shripati’s original contention that Kadambini was an impostor had a logical assurance of reality but Kadambini’s own assertion defies all logic. This can even be seen as her desire to go beyond logic constructed for social convenience,

Sister, it’s me, your own Kadambini, but I’m no longer alive, I’m dead.

The final destination of her journey, following a cyclical pattern ends in her in-laws’ house as a reaffirmation of social codification that a woman’s final resting place is ideally her father-in-law’s house. What follows on the level of events is quite similar to her experience at her friend’s house. She is denied the access to her only point of affection and her entire being is rejected. However the difference is easily perceptible in her reactions to the acts of rejection. While in Jogmaya’s house she asserted her super-naturality, in her own house she repeatedly begged to be considered alive. This was entirely because, coming back to the position of her initial departure, she was acutely aware of the affection and intimacy she felt for young child. Her sense of reality is dependent on her ability to feel and express emotions, something that occurred to her in her intimate moment with her surrogate son. What was silent in her gets eloquent but she is unable to understand the dichotomy.

The last violent act of hurting herself and finally jumping into the pond becomes not just a plea to convince the external personalities but also to reassure herself of her belief. The transformation of Kadambini from a woman of the household who could be taken for granted to a powerful demonic apparition demanding panic stricken requests with folded hands, is entirely a psychological one. In this context one can revert back to Freud’s idea in “The Uncanny”:

“We can also speak of a living person as uncanny, and we do so when we ascribe evil intentions to him. But that is not all; in addition to this we must feel that his intentions to harm us are going to be carried out with the help of special powers.”

Ironically, the special power that Kadambini was supposed to be filled with was the same factor that made her powerless. Therefore, as she was appealed to with folded hands,

Satish is the only son of our line; why have you cast your eye on him… Since you have left this life, break off these earthly bonds.

She was never given a chance to use language in her defense but act it out to prove her case. Perhaps Kadambini understood that to go beyond that concept of her demonic status she needed to come down to the level of mortality, by dying. Transformation and de-familiarization of the known, in being a psychological condition, is made to be undone through the only act of control on the part of Kadambini. Her action is the ultimate proof that a woman’s words are not good enough to challenge or defy the age-old structures embedded in the psyche of those who inhabit society, her silence through death is a better generator of awareness and this is how in “The Living and the Dead” we also see a counter discourse of Freud– not of death deflected as silence but of silence necessitating death for expression and validation. The entire journey of Kadambini after her escape from the crematorium hut becomes emblematic of her constant groping for meaning of death and to assign a fixed status to her troubled state beyond the comprehension of normality.

Notes

- Sigmund Freud extensively deals with this theme in his essay The Theme of the Three Caskets, published in Collected Papers, 4, 244-56. Trans. C.J.M. Hubback. New Delhi: Shrijee’s Book International, 2003.

- The symbolic, through language, is “the pact which links… subjects together in one action. The human action par excellence is originally founded on the existence of the world of the symbol, namely on laws and contracts” (Freud’s Papers230).