Implied Author: Wayne C Booth’s Unique Idea

Implied Author: The Basic Qualities

Booth prefers the term “implied author” over “voice’, in order to indicate that the reader has a sense, not only of the timbre and tone of a speaking voice, but of a total human presence. The implied author, although related (but not equal to) the actual author, is part of the fiction. The author gradually brings it to life in the course of composition. The implied author plays an important part in the progress of the narrative.

A closer look at Booth’s definition of implied author reveals four major characteristics:

· Ideal

· Created

· Literary

· Exercise of choice

Why Ideal?

By Whom Created?

Booth emphasizes that the implied author is a construct. For instance, in Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess”, the narrator is surely not Elizabeth Barret’s loving husband but an insanely arrogant murderous misogynist. An author need not be recognizably subjective but the implied author is thoroughly engaged with life and does not conceal his/her judgement on the selfish, the foolish or the cruel. Even in novels with undramatized narrators, an implicit picture of an author is created who stands behind the scenes. Booth gives the example of Hemingway’s “the Killers” to show how “there is no narrator other than the implicit second self that Hemingway creates as he writes” (151).

Whose Exercise of Choice?

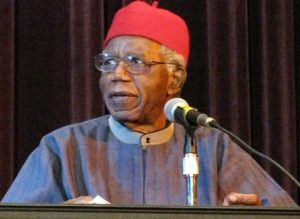

Consequently, one can understand what Booth meant by his insistence on the narrative agency as capable of exercising choice. Conrad has been thoroughly criticized as a racist by Chinua Achebe in “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’”:

“Can nobody see the preposterous and perverse arrogance in thus reducing Africa to the role of props for the break-up of one petty European mind? But that is not even the point. The real question is the dehumanization of Africa and Africans which this age-long attitude has fostered and continues to foster in the world. And the question is whether a novel which celebrates this dehumanization, which depersonalizes a portion of the human race, can be called a great work of art. My answer is: No, it cannot.”

The readers may contend that the narrative is filtered through Marlow, a fictive narrator. However, one may also observe the authorial silence and indifference to any refutation of Marlow’s conception. This may be interpreted as Conrad’s self-equation with Marlow. The reader is in no position to pass judgement on the author solely based on this. The very fact that Marlow chooses to see the native Africans as beasts (victimized but bestial) is a revelation of Marlow’s temperament. Similarly, the description of Kurtz’s cottage is filtered through Marlow’s eyes. His choice of putting Kurtz in a state of crisis presupposes his own sense of economically advanced western civilization as capable of saner existence. However, one must not equate narrator with implied author. Perhaps, the agency which Achebe calls racist is neither Marlow nor Conrad but the implied author of “Heart of Darkness”.

How Literal?

For instance, the reader becomes aware that the narration of Ford Madox Ford’s “The Good Soldier” is fraught with the mis-cognition of John

Implied or Inferred?

Implied Author: Is it Relevant at all?

Some critics dismiss the usefulness or even existence of the implied author. However, implied author is a key to an understanding of the author as well and should not be disregarded. Just as authorship can be implied, readers also may be implied by the stance the narrator takes towards values in the text. As Roland Barthes maintained, the “inscribed” reader’s responses may be intended to guide our responses.

Sources:

Achebe, Chinua. “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness'” Massachusetts Review. 18. 1977. Rpt. in Heart of Darkness, An Authoritative Text, background and Sources Criticism. 1961. 3rd ed. Ed. Robert Kimbrough, London: W. W Norton and Co., 1988, pp.251-261

Booth, Wayne C. The Rhetoric of Fiction. Univ. of Chicago Pr., 2008.

Chatman, Seymour. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film. Cornell University Press, 2007.

Photograph Courtesy:

Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.